By now, we have all endured several weeks of various “Stay at Home” Orders issued by state and local governmental agencies, and we are beginning to adapt somewhat to the new paradigm – and soon we will have to start adjusting to a new way of life, the staged “re-openings” of various parts of the United States and the world. It’s time to start thinking about how these next stages will affect your physical operations over the next several months to a year. Many businesses are also starting to think about how to incorporate pandemic preparedness into their future business planning models.

From a health and safety (H&S) perspective, this largely includes protecting your workforce from exposure to infectious diseases such as the SARS-CoV-2 virus while they are performing work. Previously, we’ve discussed some best management practices around reducing potential exposure in the office and commercial real estate buildings, as well as the industrial workplace.

OSHA Guidance

These posts focused largely on how to implement the best practices recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the workplace. In this post, we are going to focus on some more recent guidance issued by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regarding COVID-19. OSHA has issued several memorandums and guidance documents related to the risks of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and employer obligations, as there are no specific OSHA standards regarding such exposure risks. Among the standards OSHA has cited that may be relevant are:

- 29 CFR 1910 Subpart I – Personal Protective Equipment (PPE); and,

- Section 5(a)(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act of 1970, 29 USC 654(a)(1) – General Duty Clause

OSHA has cited various other standards as having potential relevance as well, including those related to hazard communication, sanitation, and illness reporting. OSHA further has noted that the Bloodborne Pathogens standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) requirements do not typically include respiratory secretions such as those from SARS-CoV-2, however, it provides a good framework for controls that be used for some sources of the virus (e.g., exposures to bodily fluids).

To help businesses navigate the overlapping but not fully applicable regulations, OSHA has issued a Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19, which is based on the principles of hazard recognition as they apply to COVID-19.

Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response Plan

At the onset of an outbreak with pandemic potential, the uncertainty and complexity of the situation require a way to assess risks to employees and the business. OSHA’s guidance includes a recommendation for an Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (IDPRP) to reduce the adverse impact of a pandemic outbreak, by implementing procedures designed to provide a uniform course of action which is based on the levels of risk associated with the worksite and job tasks performed by workers.

The primary objectives of an IDPRP include:

- Ensuring worker safety and security;

- Providing compliance with applicable OSHA regulations and allowing for incorporation of additional governmental guidance or orders;

- Establishing a pandemic crisis management team that will oversee implementation of the IDPRP, track and interpret emerging guidance, and adjust the IDPRP as needed;

- Preserving activities critical to business functionality and operations;

- Providing mechanisms for identifying and communicating critical information and messages to personnel, such as:

- Disease surveillance information (outbreaks) and recom- mended actions from recognized health agencies such as the CDC and World Health Organization (WHO);

- federal, state, and local health departments;

- Changes in corporate policies regarding pandemic response actions;

- Changes in risk assessments regarding activities being conducted in the workplace as new information arises; and,

- Contact information for relevant company (e.g., the crisis management team members).

Classifying Worker Exposure to SARS-CoV-2

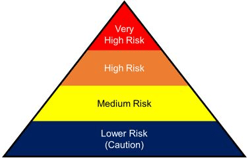

Worker risk of occupational exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus varies based in part on industry type. OSHA has provided guidance using the Occupational Risk Pyramid for COVID-19, which divides exposure risk level into categories of very high, high, medium, or lower (caution).

- Workers in very high exposure risk jobs involve those with exposures to known or suspected sources of COVID-19 during specific medical, postmortem, or laboratory procedures. Workers in this category involve doctors, nurses, dentists, paramedics, emergency medical technicians, healthcare or laboratory workers collecting or handling specimens or morgue workers performing autopsies.

- High exposure risk jobs are those with high potential for exposure to known or suspected sources of COVID-19. Workers in this category include healthcare delivery and support staff, medical transport workers or mortuary workers involved in preparing bodies for burial or cremation that are known to have or suspected of having COVID-19 at the time of their death.

- Medium exposure risk jobs are those that require frequent and/or close contact (within 6 feet) of people who may be infected with SARS-CoV-2 but who are not known to be infected with COVID-19. Workers in this category may have contact with the general public or coworkers in areas where there is ongoing community transmission. These workers may be employed in high-population-density work environments or in a high-volume retail setting.

- Workers in lower exposure risk jobs are those who are not required to be in contact with people known to be, or suspected of being, infected with COVID-19, nor frequent close contact with (within 6 feet of) the general public or coworkers. Workers in this category have minimal contact with the public and other coworkers during their normal work routines. Examples include:

- Remote workers (those working from home);

- Office workers who do not have frequent close contact with coworkers, customers or the public;

- Manufacturing and industrial facility workers who do not have frequent close contact with coworkers, customers, or the public;

- Healthcare workers providing only telemedicine services;

- Long-distance truck drivers;

Most manufacturing jobs will fall in the lower exposure risk level or, occasionally, medium exposure risk level – as such, the below highlights control measures that can be used in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Workplace Controls

Occupational health and safety professionals use a method called the “hierarchy of controls” when evaluating methods to reduce workplace hazards. The best controls involve removing the hazard rather than relying on worker behaviors – such as following procedures or using personal protective equipment (PPE) – to reduce their exposure.

These controls, starting with the most effective though the least effective, are: Elimination, Substitution, Engineering Controls, Administrative Controls, and PPE. When determining which controls are best, employers often consider matters such as ease of implementation, likely effectiveness, and cost. Elimination and Substitution are unlikely to be an option in most manufacturing settings and PPE that has been demonstrated to protect workers from exposure is in short supply; as such, many companies are employing a combination of administrative and engineering controls to protect their workers from exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, such as those outlined below.

- Engineering Controls are used to isolate workers from work-related hazards and reduce hazards without relying on worker behavior. Engineering controls to consider during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic include increasing ventilation rates and/or increasing the percentage of outdoor air that circulates into the system, or if possible installing high-efficiency air filters. If feasible, and without increasing the risk of other hazards in the work environment, temporary physical barriers, such as clear plexiglass shields, can be installed in between work-stations or in areas where employees need to stand in close proximity to one another, e.g., when operating production equipment. Shipping and receiving departments can also employ the use of such shields in areas where drivers and shipping clerks interact frequently, or a temporary “drive-through” area can be set up using a guard shack or similar.

- Administrative Controls require an action be taken by the worker or employer and typically involve changes in policies or procedures to reduce or minimize exposure to a hazard. They rely more heavily on personal behaviors – not only on the part of workers, but also those of supervisors and managers. Examples seen in the media have included encouraging workers to work from home whenever possible, encouraging virtual meetings instead of face-to-face meetings, and discontinuing non-essential travel. In a manufacturing setting, this is more challenging. To be successful, policies and procedures need to include checks and balances, frequent communication, and personnel training. For example,

- Not only encouraging sick workers to stay at home, and also communicating what showing signs of being “sick” looks like;

- Establishing extra shifts or alternating workdays to reduce the number of workers in the facility at a given time and ensure supervisors explain to their teams why shifts are changing;

- Including up-to-date information and training on risk factors and protective behaviors (e.g., hand washing, cough etiquette, removal of PPE) as part of company communication as well as routine safety meetings;

- Ensuring workers are trained on what, if any, of the routine PPE they use can protect them against exposure, and how to remove PPE that may have come into contact with potential sources of the virus, as well as helping them understand what would not be considered PPE for protection against the virus;

- Implementing safe work practices such as requiring routine hand-washing or disinfecting and cleaning of ‘high-touch’ surfaces, and installing portable hand-washing stations, setting out no-touch trash cans, and ensuring disinfectant solutions and disposable towels are readily accessible (and replenished) in these areas.

The most important thing in implementing risk controls at your workplace is to follow the hierarchy of controls according to risk – consider whether new procedures are sufficient, or whether there are cost effective engineering controls that might provide better protection.

OSHA Recordkeeping for Recording Cases of COVID-19

Many employers have been asking what needs to be done under the OSHA recordkeeping standard if a worker is infected with COVID-19 and whether this would be considered a recordable case. According to OSHA’s Enforcement Guidance for Recording Cases of Coronavirus Disease for 2019 dated April 10, 2020, COVID-19 would be a recordable illness, and employers are required to record cases of COVID-19 if: 1) the case is a confirmed case as defined by CDC; 2) the case is work-related as defined by 29 CFR 1904.5; and 3) the case involves one or more of the general recordkeeping criteria identified in 29 CFR 1904.7.

Given that it may be difficult for employers to confirm whether a case of COVID-19 is work-related, particularly in areas where there is on-going community spread, OSHA has indicated that it will not enforce 29 CFR 1904 to make COVID-19 “work-relatedness” determinations for facilities that are not emergency response organizations, in the healthcare industry, or correctional institutions, except under circumstances where:

- OSHA determines that there is objective evidence that a COVID-19 case may be work-related, e.g., if a number of cases develop among workers who work closely together and no other explanation is apparent; and

- Such evidence was reasonably available to the employer.

OSHA created this policy with the intention of encouraging employers to focus on proactive measures to protect employees and reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the workplace. Using the risk classification and implementation of suitable and overlapping engineering and administrative controls described above should be the main focus of employers.

The Next Pandemic

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic is not likely to be the last pandemic we experience. Companies can help maintain business continuity by using lessons learned during the last several months to be better prepared for the next pandemic, or even for a resurgence of COVID-19. While preparing an IDPRP or similar mechanisms to address your facilities’ risks of and controls around the SARS-CoV-2 virus is the most critical task at the moment, H&S Managers are encouraged to consider how different their IDPRP might look in the case of a more virulent strain or more persistent virus. Consider evolving the IDPRP into a pandemic preparedness plan, which could allow for coordinated response actions based on the nature of the disease and stages of an outbreak or pandemic, as well as having procedures and supplies in place to protect your workers and facilities.

Additional information can be found at:

https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/covid-19/standards.html

https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3990.pdf

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/businesses-employers.html

.jpg)